Diffusionism

A group of Austro-German anthropologists, led by Fritz Graebner and Wilhelm Schmidt, rejected 19th-century evolutionism in favour of a belief that a few core cultures influenced all later societies. This diffusion, or spreading, of culture traits was believed to be the basic force in human development. By analysing the cultural behaviours and aspects of a society, a diffusionist believed that he could determine from which core culture that society derived its civilization. Because the diffusionists called the original ancient civilizations "kulturkreise" (or "cultural clusters") they were also known as the kulturkreise school of anthropology.

A British group of diffusionists, led by Grafton Elliot Smith and William J. Perry, argued that only one civilization was responsible for all cultural development. They believed that the civilization fitting their theory was ancient Egypt and that ideas such as irrigation, kingship, and navigation were spread from the ancient civilization along the Nile throughout the world by voyagers who were seeking precious jewels. This theory was called the Manchester, or heliocentric (self-centred) school of thought. The metaphor of the sun suggested that all cultures radiated from but a single source.

Although the diffusionist approach to anthropology was dominant in early 20th-century Europe, it was thought an inadequate point of view by later scholars. They claimed that it disregarded important geographical and psychological differences in culture.

Functionalism

After World War I a school of thought developed that rejected historical approaches to the study of cultures. A leading proponent of this theory was Bronislaw Malinowski, a Polish-born British anthropologist. He believed that to understand a culture one must perceive its totality and the interrelationship of all its parts, much as if culture were a machine and the individual traits the cogs and gears that made it operate. Culture was to be interpreted at one point in time. The age of the elements composing it were of no importance. What mattered was the function the traits performed at any given time. Functionalism provided the field of anthropology with valuable contributions in the analysis of family, kinship roles, rites of passage, and political organization.

Closely related to functionalism was a theory proposed by the American anthropologist Ruth Benedict in the 1930's. She believed that each culture had, over the ages, given its members a unique orientation toward reality that determined how members saw and processed information from their environment. She believed it was necessary to study such mental or psychological conditioning to see how it functioned in a given society.

Structuralism

Another influential 20th-century school of thought is structuralism, which is similar in many ways to functionalism. Its leading early proponents were the British anthropologist A.R. Radcliffe-Brown and Claude Levi-Strauss, a Belgian-born French ethnologist. They asserted that by taking all of the many aspects of a society into consideration one could arrive at a clear structural description, or model, of it a model that the members of the society themselves are not fully aware of.

Radcliffe-Brown stated that all aspects of a society exist in order to maintain the social structure of the society. Levi-Strauss was convinced that a culture, like a language, has a structure that can be similarly analysed The model that the anthropologist constructs is correct when it can account for all the observed data on a given society. One of the difficulties with structuralism is that it presumes a static condition and may find difficulty in taking historical changes into account.

Neo-evolutionism

Since World War II there has been a revival of interest in evolutionism. The American anthropologist Julian Steward believed that similar stages of development are apparent in the cultural histories of various civilizations. His theory, termed "multi linear evolution" or "specific evolution," states that such similarities develop quite independently. A comparison of the sequences of change in sets of cultures should reveal regular patterns of change that are common to all of them.

Another American, Leslie White (1900-75), viewed culture as an inevitable natural process that develops from mankind's increasing ability to harness energy and use it effectively. The social and psychological make-up of a culture is therefore determined by its technology. From the work of Steward and White has come the term cultural ecology. This school of thought states that because a culture tends to reflect efficient use of the environment, similar environments will inevitably produce cultures that are similar.

HISTORY

At least since the earliest times of the Greeks the study of mankind has been a major intellectual endeavour, a subject for speculation and for investigation. Philosophers, such as Plato and Aristotle, speculated on what it meant to be human and on what mankind's place was in nature and in the universe. Herodotus, on the other hand, was an investigator. In Western society he is considered the first historian and the first ethnologist.

In the 5th century BC he travelled over much of the known world, to Libya, Egypt, Syria, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, Thrace, Macedonia, Scythia, and eastward into what is now southern Ukraine and Russia. The observations he made on his travels were published in his 'History'. Along with his narrative of the Persian Wars and other events involving the Greek city-states, he described the customs, social habits, religions, and political structures of many of the peoples he visited on his travels.

There were other ancient precursors of anthropology. In the 1st century BC the Roman philosopher Lucretius, in his 'On Nature', discoursed on the origin of religion, the arts, language, the division of labour, and the differences between the sexes. In AD 98 the Roman historian Tacitus wrote his 'Germania', an anthropological study of the Germanic tribes to the north of the Roman Empire.

In the Middle Ages the Christian religion dominated the thought of Europe. Mankind was not viewed as existing for itself. Mankind's status was that of creatures of God whose ideal behaviour reflected religious values. During the period called the Renaissance a change in attitude took place. Poets, painters, and scholars gained a renewed interest in the classical writings of Greece and Rome. They rediscovered the notion of studying mankind for its own sake.

It was during the 16th century that the term anthropology was coined and used by philosophy teachers in German universities. Anthropology was understood to be the systematic study of man as a physical and moral being. From the 16th to the beginning of the 19th century anthropology remained within the province of philosophy. Among the many writers who reflected upon the nature of man were the Frenchmen Michel de Montaigne, Jean Bodin, Rene Descartes, and Blaise Pascal; the Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza; the English philosophers John Locke and David Hume; and the German philosopher Immanuel Kant.

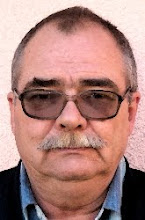

Georges Louis Leclerc Buffon, comte de (1707-88), French philosophic naturalist and writer ('Natural History').

With the work of the French naturalist Georges Buffon the divergence of anthropological studies from philosophy began to take place. He devoted two volumes of his 44-volume 'Histoire naturelle' (Natural History), published in the years 1749 to 1804, to man as a zoological species. Since that time anthropology has continued to diversify its approaches. Scholars have also maintained the necessity of using data from other sciences in their work.

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, (1752-1840), German naturalist and anthropologist, born in Gotha; founded science of anthropology; placed comparative anatomy on scientific basis.

Physical anthropology developed as a separate science under the influence of Johann F. Blumenbach in Germany. He was the first scholar to divide humanity into races. By the middle of the 19th century geologists and archaeologists had thrown a good deal of light on the age of the Earth and of human societies. For the first time, anthropologists saw the possibility of tracing mankind's origins into the very remote past.

Some Major Anthropologists

Some prominent persons are not included below because they are covered in the main text of this article or in other articles.

Blumenbach, Johann Friedrich (1752-1840). The founder of physical anthropology. Born in Gotha, Germany, on May 11, 1752. Professor of medicine at Gottingen University. The first scholar to show the value of comparative anatomy in the study of man's history. Divided mankind into five families, or races. Died on Jan. 22, 1840.

Johanson, Donald C. (born 1943). A leading American anthropologist. Born in Chicago on June 28, 1943. Curator of physical anthropology at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. In Ethiopia in 1970s, he found the oldest fossils showing man's bipedal stature and locomotion.

Kroeber, Alfred Louis (1876-1960). One of the major American anthropologists in the first half of the 20th century. Born in Hoboken, N.J., on June 11, 1876. Earned his doctorate under Franz Boas at Columbia University in 1901. Author of one of the first general texts in anthropology (1923). His field investigations centred on the Indians of California. Died in Paris on Oct. 5, 1960.

Mauss, Marcel (1872-1950). French anthropologist and sociologist. Born in Epinal on May 10, 1872. A nephew and student of pioneer sociologist Emile Durkheim. Professor of primitive religion at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes in Paris. A major influence in the field of ethnographic studies. Died in Paris on Feb. 10, 1950.

Morgan, Lewis Henry (1818-81). American ethnologist and pioneer in the study of kinship systems. Born near Aurora, N.Y., on Nov. 21, 1818. His major work, 'Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family' (1871), inaugurated the scientific study of kinship. Died in Rochester, N.Y., on Dec. 17, 1881.

Radcliffe-Brown, Alfred Reginald (1881-1955). British social anthropologist. Born on Jan. 17, 1881, in Birmingham. Educated at Trinity College, Cambridge. Did fieldwork in the Andaman Islands and in Western Australia. Taught at University of Sydney, the University of Chicago, and Oxford University. His major contribution was in systematizing social structures of simple societies. Died in London on Oct. 24, 1955.

Sapir, Edward (1884-1939). American linguist and anthropologist. Born in Lauenburg, Pomerania (now in Poland), on Jan. 26, 1884. Educated at Columbia University, where he earned his doctorate under Franz Boas. Taught at the University of Chicago and at Yale University. His most significant contributions were in the study of American Indian languages. Died in New Haven, Conn., on Feb. 4, 1939.

Tylor, Edward Burnett (1832-1917). English anthropologist credited with originating the scientific study of culture. Born in London on Oct. 2, 1832. Investigation of primitive societies led him to develop the theory of an evolutionary, progressive relationship between preliterate and literate, technologically advanced cultures. His major work was 'Primitive Culture' (1871). Died in Wellington in Somerset, on Jan. 2, 1917.

BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR ANTHROPOLOGY

Alland, Alexander, Jr. To Be Human (Random, 1981).

Benedict, Ruth. An Anthropologist at Work (Greenwood, 1977).

Benedict, Ruth. Patterns of Culture (Houghton, 1989).

Boas, Franz. Race, Language and Culture (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1988).

Campbell, Bernard. Humankind Emerging, 4th ed. (Scott Foresman, 1985).

Coon, C.S. and others. Races: A Study of the Problem of Race Formation in Man (Greenwood, 1981).

Coon, C.S. The Story of Man, 2nd rev. ed. (Knopf, 1962).

Fisher, M.P. Recent Revolutions in Anthropology (Watts, 1986).

Foster, G.M. and others. Medical Anthropology (Random, 1978).

Gregor, A.S. Life Styles: An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology (Scribner, 1978).

Haviland, William. Cultural Anthropology, 5th ed. (Holt, 1987).

Johanson, Donald and Maitland, Edey. Lucy: The Beginnings of Humankind (Warner, 1982).

Jolly, Clifford, ed. Early Hominids of Africa (St. Martin, 1978).

Malinowski, Bronislaw. Scientific Theory of Culture (Univ. of N.C. Press, 1944).

Mead, Margaret. Coming of Age in Samoa, reprint (Morrow, 1971).

National Geographic Society. Primitive Worlds: People Lost in Time (National Geographic, 1973).

Steward, J.H. Theory of Culture Change (Univ. of Ill. Press, 1972).

White, L.A. The Concept of Cultural Systems: A Key to Understanding Tribes and Nations (Columbia Univ. Press, 1975).

No comments:

Post a Comment